FROM THE RECTOR

A Spirit in Common

I spent the bulk of this week in the middle of Mississippi, taking part in what is known as the Gathering of Leaders. Begun just over ten years ago, it’s a regular gathering of Episcopal priests from around the nation for retreat and peer-led learning. I try to attend every 2-3 years to learn best practices, hear what is animating other leaders across the country, and re-connect with far-flung colleagues.

Each year the gathering is centered on a theme that informs the theological teaching and practical application presentations. This year, deeply aware of the state of our nation, the theme for this Gathering was, “Unity and Division.”

As is often the case, part of the gift of this gathering was found in wide variety of contexts that we are a part of—we hailed from places like Texas, Rhode Island, Ohio, Washington, and Florida. We serve in rural, suburban, and urban communities. And we lead churches that are reflective of the communities that span the spectrum.

So it was not unexpected to hear other leaders talk about the challenge of pastoring Christian communities who struggle with deep political division. How does one preach with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other, knowing that as a nation we often seek out sources of information that reinforce our already formed opinions? What is the role of a Christian congregation in times of some of the deepest political and social division this country has experienced in decades?

It was in one of the presentations by a priest from Birmingham, Alabama that something opened up for me. When many of us consider what unity is, or perhaps how it is achieved, we often conceive of unity as taking place when we have come to a state of common mind. What if, this priest suggested, we instead came to view unity as a state of common spirit?

My understanding of the history of the Christian Church is that in every era we have been at odds with each other. From the beginning of this religious expression it has been rare to be of a common mind. Whether it was Paul and Peter in the 1st century, or the struggle over the Creeds in the 4th and 5th centuries, or the Great Schism of East and West in the 11th century, or the Reformations in the 15th century, rarely has a common mind been found.

And. That should not mean that unity among Christians is impossible. What if the oneness that Jesus implores his followers to seek in John’s Gospel is instead found through a common spirit of consideration and of compassion? Or known in a spirit of willingness to be converted as much as to convert, as to understand as to be understood?

What if the source of our unity wasn’t to be found in political unanimity but instead through forbearance and love within our differences? What kind of unity might be able to flourish? My sense is that could be the kind of unity that can change the world.

Peace,

Phil+

From the Senior Warden

Vestry Reflections

Vestry Reflections

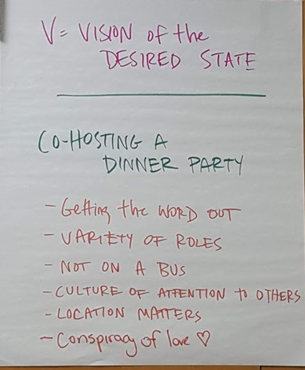

“Is coming to All Souls more like riding the bus or co-hosting a dinner party?”

It’s not a riddle. It’s how Emily opened her exercise for the vestry at our last meeting on April 10.

Recently, the vestry committed to tend to how we welcome one another at All Souls. At our retreat in February, we heard that some visitors and new members have been neglected or sidelined in our rush to greet those we already know, even getting trapped in the pews between members who were greeting others.

While Emily does a remarkable job of engaging newcomers, one person can’t be responsible for a whole congregation’s hospitality. So Emily asked us, what is it like to host someone for dinner? There are many ways of making people feel at home and welcome, but we would never invite someone into our house and then studiously ignore them! We asked ourselves, when we come to church, do we relate to one another more like co-hosts of a good party, or more like strangers forced to share space on the bus?

Then we walked through Phil’s favorite College for Congregational Development’s tool, the Beckhardt Change Model. We interrogated our own resistances to change – we barely get to see the people we already know, we aren’t all extroverts, etc – as well as our dissatisfactions with the way things are – we miss out on potential new members, and we don’t carry out our commitments to radical hospitality.

In the end, our vision includes a variety of ways of welcoming, from hospitality to the peace to official greeters, engaging all of us in a culture of attentiveness to others, and, to quote Howard’s experience of arriving at All Souls, a “conspiracy” to welcome both newcomers and longtime friends. Look for more from us in the coming months on how we plan to live that out as a vestry, and invite you to join us.

In other vestry business, Kaki took us through a spiritual reflection on Jesus’ Palm Sunday return to Jerusalem, asking us what we might need to be courageous for. Ed Hahn and Kirk Miller presented updates on the Parish House Project, including architectural schema and renderings of how the SAHA building will look from the street and from All Souls.

Our next meeting will be Wednesday, May 15 at 7:30 pm in the All Souls Common Room.

— Laura Eberly

HOLY REFLECTIONS FROM A HOLY WEEK

On Good Friday afternoon, seven wise and brave souls shared how their own stories connected with the Stations of the Cross. Today and in coming weeks, we will be offering some of those reflections, in no particular order, but with much gratitude.

“Mother, here is your son,” “Son here is your mother” (John 19:26-27)

“Mother, here is your son,” “Son here is your mother” (John 19:26-27)

In these words, as he is dying, Jesus is bringing the Beloved Disciple together with his mother as he will no longer be able to be her kin or to support her. For me these words are resonant.

The past few years have been a long season of loss for me and for my family. Two of the biggest losses were losing my father and my brother-in-law.

My father very suddenly a year and a half ago when a tumor exploded and we discovered he had lymphoma at the age of 69.

My brother-in-law this past Thanksgiving after two and a half long years of chemotherapy and 3 weeks of home hospice at the age of 49.

My mom and little sister are now both widows, and my niece and nephew, 7 and 5, lost their dad and actually both of their grandfathers within a 14-month period.

Some families, I imagine, draw closer during tragedy, focus on what matters, value their precious time together. Mine, not so much.

With my family – gloriously dysfunctional as we are – it just felt like we added cancer, death, financial instability and stress on top of all the problems that were already there. While there have been definite moments of joy, it has been a very painful road reorganizing and reimagining who my family is.

On this side of those losses, life is returning, and we are rearranging what it means to be family, who plays what role and when, and how we raise these 2 kids in a world that is profoundly unfair, and yet still beautiful.

What I have been reflecting on a lot, is that what better enables families like mine to deal with situations like this are institutions like the church; community that has a set of standards and practices, ways of being and support. And this is the second part of my story.

Mary was the biological mother of Jesus of Nazareth, but Mary is also the Theotokos, the God bearer, the Mother of the Church. The theologian Stanley Hauerwas says of this particular moment: “At this moment, at the foot of the cross, we are drawn into the mystery of salvation through the beginning of the church. Mary, the new Eve, becomes for us the firstborn of a new reality, of a new family, that only God could create”

I have had a four decades long conflicted relationship with Christianity, a relationship of deep difficulty, deep love, and deep struggle. Sometimes that has included membership in a particular congregation, sometimes not.

The death of my father and brother-in-law reordered that relationship yet again.

I gave the eulogy for my dad at the pulpit of his church that does not ordain women, that is challenged in accepting LGBTQ people, and with which I and my siblings have had long-held tension. And yet. They provided food for my family, sat with my father, re-sided my mother’s house after my father died even though she is not a member of their church or their tradition.

When my very not religious brother-in-law died we didn’t know who could preside at his burial amidst great religious differences across families. The chaplain at the Catholic hospital where both he and my father received treatment generously held our family’s grief that day in ways for which I am still profoundly grateful.

This church and many others across the country prayed for my family by name, people who they did not know.

“Mother here is your son,” “Son here is your mother” – Jesus is extending the bonds of kinship beyond blood, beyond tribe, beyond “my people”, and that is what I understand Christianity to be about. We are called to ever expand the table: to whom do we belong, and who belongs to us? That admittedly aspirational but radical inclusivity is where I find my hope.

Last week I took my sister and her kids away for the weekend. As we were checking out of the hotel my niece ran up to the counter with me and my sister and nephew were a few steps behind. The clerk was confused, and wondered out loud who the children belonged to. I instinctively said, “they’re both hers”, then I looked down at my niece and said, “well, actually, you belong to me too, just in a different way.”

– Anna Eng

Last Words

“I am thirsty” (John 19:28)

Like many other people, I’ve always been fascinated with “Last Words.” From Goethe’s urgent demand, “More Light,” to Gertrude Stein’s “What is the answer? Alright then, what was the question?” Emily Dickinson’s illuminating warning, “I must go in, for the fog is rising.” And Ulysses S Grant’s offering, “There was never one more willing to go than I am.” Followed by his nearly Christ-like plea, “Water.”

Like many other people, I’ve always been fascinated with “Last Words.” From Goethe’s urgent demand, “More Light,” to Gertrude Stein’s “What is the answer? Alright then, what was the question?” Emily Dickinson’s illuminating warning, “I must go in, for the fog is rising.” And Ulysses S Grant’s offering, “There was never one more willing to go than I am.” Followed by his nearly Christ-like plea, “Water.”

When Jane and I were struck by a car on Solano Avenue, I think what kept me from dying was my desperate fear that my own last words might be, “Our favorite gelato place closes in fifteen minutes.”

But in my life so far, no Last Words have occupied me more often than Jesus’s “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do,” or “Into Thy hands I commend My Spirit.” This is a gospel of obedience and aspiration. And for a young Christian, nothing is more terrifying than “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani” – “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?”

Jesus is giving up His human form, as an innocent sacrifice, because of God’s terrible need. He is suffering the greatest horror, His passionate agony. At the end He shares a most identifiable human frailty.

“I am thirsty,” He says. [Psalm 22.15]

He quotes from a poem in the Psalms, and the unwitting actors around him, the Roman soldiers, carry out the prophesy by serving Jesus sour wine on the branches of a hyssop bush.

I am poured out like water,

And all my bones are out of joint;

My heart is like wax;

It is melted within my breast;

My mouth is dried up like a potsherd,

And my tongue sticks to my jaws;

You lay me in the dust of death.

Over time, in my own struggle, I range almost daily from rigid disbelief to radical faith. I vacillate between the blunt flat ground of humanism and reason, to the attitude of faith and hope and endless love.

This year, during this time of Lent , I imagine I have gathered myself onto a cross on Golgotha, and I am one of those thieves, pulled between one thief or the other. My own thirst is unending. I can wake in the night. My struggle often finds me too full of myself, too busy with my own salvation. I cannot afford the time. I become too self-satisfied and too self-confident. I become filled with the challenging rage of the thief who says, “Save yourself, if you are the Messiah, and save us. I am embarrassed even to know of you.”

But if I can slow it all down, if I can practice silence, and quiet my mind, and focus, and follow my heart’s pulse, I can come to realize that our prayers and fasting and longing and sacrifices are not meant to imitate Jesus’s suffering, but are offered to make us alert. And willing. My thirst disappears, at least for a moment. I become filled with longing, and I want to say, with the other thief, “Remember me.”

That is the hope of Holy Week, my hope, our hope. It feels as ragged as life itself.

It feels as mysterious as Grace.

— Jack Shoemaker

Celebrating with Emily and Megan

Continuing in ADULT FORMATION

This past Sunday new offerings in Adult Formation began, and continue meeting Sundays at 10:10 am through on May 12th.

Christian Hope: Imagining the “Last Things,” with Dr. Scott MacDougall in the Parish Hall

When Christians think about the “last things,” there is a tendency to either roll one’s eyes at Left Behind–influenced fantasies about “the end of the world,” or to imagine rather hazily some form of personal life after death involving a “soul” that continues beyond the life of the body, or to ignore the topic all together because it is too strange, speculative, or embarrassing. What we lose in this, though, is a tremendous source of hope that has energized Christians for thousands of years. In this series, we will explore what theologians call eschatology, the theology of “the end of things,” in order to rediscover what scripture and tradition actually tell us about the final state of creation—including human beings—and how this can be a source of tremendous hope that energizes our Christian spirituality and practice now.

Series for Newcomers and New Members

If you are new to All Souls, have never been to a newcomer event, or are curious about becoming a member here at All Souls, you are invited to this next round of newcomer events. Next up on May 5th, we’ll host a Meet & Greet with Phil in his office. Finally, on May 12th, those of you interested in membership are invited to the home of an All Soulsian after the 11:15 service (1-3p), to meet with Phil, Liz, and Emily for lunch and a brief class on membership here at All Souls. If you have questions about any of these events, please reach out to Emily, emily@allsoulsparish.org.

The Good Book

The Berkeley Rep has offered us discounted tickets to see their new play The Good Book, running through June 9th. The Good Book weaves together three distinct yet connected stories: a devout young man struggling to reconcile his belief with his identity; an atheist biblical scholar trying to find meaning as she faces her own mortality; and the creative journey of the Bible itself—from ancient Mesopotamia to medieval Ireland to suburban America—through the many hands, minds, hearts, and circumstances that molded this incredibly potent testament to the human spirit. If you’re interested, see Emily Hansen Curran for more information.