From the Rector

Obedir

Obedir

In the past couple of months I have found inspiration in an ancient treasury, this time in the pattern of Christian life developed by the 6th century monk and abbot Benedict of Nursia.

It is hard to fully comprehend the influence that Benedict has had on the shape and structure of the Christian Church, in both the East and the West, but for today I would like to look just at one of the core elements of Benedictine communal life—the practice of obedience.

For a member of a community gathered around Benedict’s Rule of Life, obedience is one of three essential practices, alongside Stability and Conversion of Life. As a priest, a family member, and a practitioner of various forms of community, I have found obedience to be critical to communal life, and to be a practice that we often resist, usually to disastrous ends.

First, what obedience is not in the practice of the Benedictine life. Obedience is not blind assent. And it is not simply practiced in one direction, from the powerful to the powerless. These are indeed shadow expressions of obedience but bear no resemblance to the true and generative practices that obedience in Christian community demands.

To understand obedience in the Benedictine sense, we have to get to the root of the word, which in this case is from the Latin obedir. Obedir means to listen. Not control, not conform, but listen. Obedience, then, is known and practiced through listening to one another, deeply and intently. Truly listening means that we have to suspend our certainty, for out of obedience to God through one another comes new information, alternate paths, and possibly even common ground. But only if we listen.

It is my sense that we are in dire need of this kind of listening at this time in our nation. The divides of culture, class, race, and political stance seem to grow election cycle by election cycle. Exacerbated by our tendencies to group with like-minded people, and fed by social media platforms that reinforce our positions through algorithm, our cultural capacity to listen to one another will be essential to our mutual well-being.

Back to Benedict in the 6th century. In his role as the Abbot, and in the Rule that bears his name, there is radical understanding of this communal responsibility to listen to one another. The exercise of obedience, of listening for Christ in the other, was not simply about listening to those in authority, but in fact those with greater authority had a commensurate responsibility to listen to those who had less power.

My hope is that the political moment that we are in, of young people speaking and taking action in ways that haven’t been seen in a half century, will be an example of the deep listening of obedience. The walk-outs that took place in middle schools and high schools yesterday around the East Bay and throughout the nation, will hopefully be an opportunity for all of us, regardless of political stance, to pay attention.

By no means do I have the sense that all of the youth in the United States are of one mind. But it is clear to me that many, many of them are using their feet and their words to tell us something. It would be easy to dismiss their voices as naïve or ill-informed. But Benedict’s call to obedience, to listening, would say otherwise. Conversion of our common life may well be on the horizon, but in this moment, in the spirit of St. Benedict, it is our responsibility to listen.

Peace,

Phil+

Reflections for Lent

Salvage

An excerpt of this reflection was first published as part of our Humans of Lent project. Here is Sarah’s reflection in its entirety.

Lent occupies a strange and powerful place in my life. For many years as an adult, I privately thought of myself as a “Lenten Christian;” you wouldn’t catch me in a church any other time of year. Growing up, I barely knew what Lent was, as I was raised in a tradition that was highly suspicious of ritual and all its trappings. In the Reformed churches of my childhood, anything that smacked of mindless form, of empty repetition, of matter taking precedence over mind—of cough, cough, Roman Catholicism—was bad news.

Between the severity of the tradition on the Dutch side of my family and the evangelical bent on the American side, I was done by the time I was twelve years old. Christianity, as far as I could tell, harmed everyone it touched, from my traumatized family, to my queer friends, to every society that had ever been conquered, colonized, and missionized in the name of Jesus. As a committed agnostic and occasional atheist, I spent the next twenty years trying to understand my inheritance in a scholarly mode, a secular inquisitor, laboring to discern whether anything, at any of these levels, could be recuperated, to see whether there was anything left to salvage.

I caught my first glimpse of salvage as a student in London, in the liturgical rhythms of the Anglican university I had unwittingly chosen to attend. It started silly and small, with Pancake Day in the Student Union (fine, I can get behind that), inexplicably smudged foreheads (should I tell them?), classmates giving up chocolate for Lent (like a half-baked Ramadan? Huh. Okay then.), and then with a friend who brought me to Holy Week services at her Anglo-Catholic parish. I didn’t even know what Maundy Thursday was until I sat there, momentarily stirred by incense and chant (Oh, this is about the Last Supper! Right, that makes sense)—stirred until something jostled, and then suddenly broke loose, when I remembered what happened at the Last Supper, and what happened immediately after it. An obscure space swelled up inside me like a balloon, putting pressure on my ribs, constricting my throat, leaving me gasping for air, as I cried and cried and cried and cried. Fortunately, my friend understood, and let me cry.

I’ve spent years trying to make sense of what happened in that moment when the thing, whatever it was, broke loose, and how it was that momentarily stepping into the story, how feeling it and hearing it and smelling it, broke it loose. For a long time, I feared probing too deeply. I avoided it—and anyway, I had things to do. But come late winter, year after year, what ever city I lived in, I inevitably found myself in the nearest Episcopal Church on Ash Wednesday, asking for the inexplicable smudge that marks entry into the place and time of dangerous contemplation, of allowing the thing to break loose, of peering into the obscure space behind it, of descending into it like Inanna, Eurydice, or Persephone (is this a feminist thing? My secular friends tease me about “Jesus doing battle with demons in the wilderness” and I scratch my head. That’s not my Lent).

Of course, if going into the dark was just about confronting our death and the deaths of those we love, that would be one thing, and it would be hard enough. But I’ve come to think that going into the dark at Lent is about more than death—our mortality is just one of our many troubled and troubling boundaries. For me, what Lent breaks loose is an awareness that my living days are shaped by my limits. My capacity to be the person I hope to be in the world is shaped by the limits of my attention, my intellect, my energy, my will, my love, my forgiveness, my ability to move and my ability to stand still, and above all the limit of my ability to repair what I have broken. I am so, so limited in these respects, and it breaks my heart constantly. Our culture doesn’t help. It is no better equipped to grapple wisely with the fact of human finitude than it is with the fact of human mortality. But as with every frightening thing, there is liberation in facing it directly.

I find the dangerous contemplation of Lent liberating because it reveals a strange paradox—the arms on the wooden cross are the arms that hold us up. Our joy and our grief, our agency and its limits, our brilliance and our frailty—these are not binary oppositions but aspects of an integrated, complex whole that encompasses and exceeds us. I want to lay the emphasis on this complex wholeness, rather than broken-ness, because I was recently brought up short in conversation with a close friend. Raised Hindu, she shuddered when she heard me explain Lent in the language of broken-ness—our brokenness, the world’s brokenness. She found it bizarre and alienating and wrong, and after sitting with it for a while, I think I understand her reaction. It might be possible that starting the conversation with brokenness is the very thing that does the breaking; it is to fixate on one dimension of our common life at the expense of all others, and so it presents a disintegrated, rather than an integrated, understanding of that common life.

And then of course it so easily becomes a mask for menacing triumphalism—you are broken, so I will fix you, whether you like it or not. There is a theological puzzle here I am still working out, but in the meantime, I’ve grown leery of my own knee-jerk tendency to explain Lent in poetic terms of brokenness. The invitation of Lent, I think, is to enter deeply not into contemplation of all things maudlin, but into the paradox that there is hope after hope dies, that there is joy in grief and grief in joy, and that we are limited and yet met with grace beyond our limits.

This knowledge has become the joy of Lent for me, as Lent has become a doorway to the liberation of living liturgically—of seasonally and collectively holding each other up in dangerous contemplation of our complex wholeness, limitations and all. Every passing liturgical year brings a new dimension of this complexity into focus, but the core is, I think, the same as it was that first Maundy Thursday in London all those years ago, the feeling of something breaking loose, and in that loosening, a resurfacing, a salvaging. At this point, I have to admit that I’ve reread Seamus Heaney’s poem Station Island so many times that I don’t know how much more I can say about salvage without plagiarizing him outright, so I’ll leave you with part XI, which includes a translation of St. John of the Cross:

Station Island, Part XI

Seamus Heaney

As if the prisms of the kaleidoscope

I plunged once in a butt of muddied water

surfaced like a marvelous lightship

And out of its silted crystals a monk’s face

that had spoken years ago from behind a grille

spoke again about the need and chance

to salvage everything, to re-envisage

the zenith and glimpsed jewels of any gift

mistakenly abased…

What came to nothing could always be replenished.

‘Read poems as prayers,’ he said, ‘and for your penance

translate me something by Juan de la Cruz.’

Returned from Spain to our chapped wilderness,

his consonants aspirate, his forehead shining,

he had made me feel there was nothing to confess.

Now his sandalled passage stirred me on to this:

How well I know that fountain, filling, running

although it is the night.

That eternal fountain, hidden away,

I know its haven and its secrecy

although it is the night.

But not its source because it does not have one,

which is all sources’ source and origin

although it is the night.

No other thing can be so beautiful.

Here the earth and heaven drink their fill

although it is the night.

So pellucid it never can be muddied,

and I know that all light radiates from it

although it is the night.

I know no sounding-line can find its bottom,

nobody ford or plumb its deepest fathom

although it is the night.

And its current so in flood it overspills

to water hell and heaven and all peoples

although it is the night.

And the current that is generated there,

as far as it wills to, it can flow that far

although it is the night.

And from these two a third current proceeds

Which neither of these two, I know, precedes

although it is the night.

This eternal fountain hides and splashes

Within this living bread that is life to us

although it is the night.

Hear it calling out to every creature.

And they drink these waters, although it is dark here

because it is the night.

I am repining for this living fountain.

Within this bread of life I see it plain

although it is the night.

– Sarah Bakker Kellogg

From the Stewardship Team

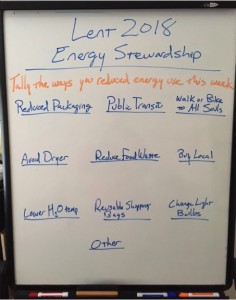

All Soulsians have been making a big effort to reduce our energy use. Over the first four weeks of Lent, we have tallied over 150 times when we have made an energy-saving choice. They range from 6 people who have changed light bulbs and lowered their hot water temperature, to the almost 50 times when people remembered to bring a reusable bag when shopping. Here is the original list of suggestions:

All Soulsians have been making a big effort to reduce our energy use. Over the first four weeks of Lent, we have tallied over 150 times when we have made an energy-saving choice. They range from 6 people who have changed light bulbs and lowered their hot water temperature, to the almost 50 times when people remembered to bring a reusable bag when shopping. Here is the original list of suggestions:

- Reduce Packaging – from buying food from the bulk aisle, to choosing toys with less packaging, look for ways to reduce the packaging that you would put directly into recycling.

- Choose Public Transit or Carpool instead of your car – make just one more trip a week in someone else’s vehicle.

- Get to All Souls – walk or ride your bike to All Souls.

- Avoid the Dryer – use a clothesline to dry your clothes; your sheets and clothes will feel and smell great.

- Reduce Food Waste – prepare and serve smaller portions to keep food out of the waste stream.

- Buy Local – Whether it’s food or sweaters or a book, the less it travels to reach you, the less energy it takes.

- Reduce Water Temperature – Many water heaters are automatically set to 140 degrees. Try lowering the setting to 120, or even 115. You may not even notice a difference.

- Carry Reusable Shopping Bags – Those grocery bags add up. Carry a bag with you to use when you make an unexpected stop at the store.

- Replace Light bulbs – Replace your incandescent and halogen bulbs with compact fluorescent bulbs (CFLs) or LED bulbs to significantly reduce the cost and energy used to light your space. Compare the Lumen ratings, not the wattage on the packages.

Parishioners also used the board to share other ways to use God’s resources more prudently. Some of these were:

- Using your own containers for leftovers when dining out.

- Stainless steel straws

- Declining straws wrapped in paper

- Lowering your thermostat and putting on a sweater

- Going vegan

- Changing to an eco-friendly cat litter

- Charging cell phone in the morning, rather than all night

Look for the Energy Use white board over the next three Sundays and share the ways in which you are taking care of God’s creation.

Another Poem in Lent

This Lent we’ve been turning our collective attention more towards the written word, with Poems for the Stations of the Cross and the visit from Christian Wiman. Time gets a little unpredictable as we approach Easter even as we remain squarely in Lent, and this poem seemed appropriate for today.

This Lent we’ve been turning our collective attention more towards the written word, with Poems for the Stations of the Cross and the visit from Christian Wiman. Time gets a little unpredictable as we approach Easter even as we remain squarely in Lent, and this poem seemed appropriate for today.

Time Problem

By Brenda Hillman

The problem

of time. Of there not being

enough of it.

My girl came to the study

and said Help me;

I told her I had a time problem

which meant:

I would die for you but I don’t have ten minutes.

Numbers hung in the math book

like motel coathangers. The Lean

Cuisine was burning

like an ancient city: black at the edges,

bubbly earth tones in the center.

The latest thing they’re saying is lack

of time might be

a “woman’s problem.” She sat there

with her math book sobbing—

(turned out to be prime factoring: whole numbers

dangle in little nooses)

Hawking says if you back up far enough

it’s not even

an issue, time falls away into

‘the curve’ which is finite,

boundaryless. Appointment book,

soprano telephone—

(beep End beep went the microwave)

The hands fell off my watch in the night.

I spoke to the spirit

who took them, told her: Time is the funniest thing

they invented. Had wakened from a big

dream of love in a boat

No time to get the watch fixed so the blank face

lived for months in my dresser,

no arrows

for hands, just quartz intentions, just the pinocchio

nose (before the lie)

left in the center; the watch

didn’t have twenty minutes; neither did I.

My girl was doing

her gym clothes by herself; (red leaked

toward black, then into the white

insignia) I was grading papers,

heard her call from the laundry room:

Mama?

Hawking says there are two

types of it,

real and imaginary (imaginary time must be

like decaf), says it’s meaningless

to decide which is which

but I say: there was tomorrow-

and-a-half

when I started thinking about it; now

there’s less than a day. More

done. That’s

the thing that keeps being said. I thought

I could get more done as in:

fish stew from a book. As in: Versateller

archon, then push-push-push

the tired-tired around the track like a planet.

Legs, remember him?

Our love—when we stagger—lies down inside us. . .

Hawking says

there are little folds in time

(actually he calls them wormholes)

but I say:

there’s a universe beyond

where they’re hammering the brass cut-outs .. .

Push us out in the boat and leave time here—

(because: where in the plan was it written,

You’ll be too busy to close parentheses,

the snapdragon’s bunchy mouth needs water,

even the caterpillar will hurry past you?

Pulled the travel alarm

to my face: the black

behind the phosphorous argument kept the dark

from being ruined. Opened

the art book

—saw the languorous wrists of the lady

in Tissot’s “Summer Evening.” Relaxed. Turning

gently. The glove

(just slightly—but still:)

“aghast”;

opened Hawking, he says, time gets smoothed

into a fourth dimension

but I say

space thought it up, as in: Let’s make

a baby space, and then

it missed. Were seconds born early, and why

didn’t things unhappen also, such as

the tree became Daphne. . .

At the beginning of harvest, we felt

the seven directions.

Time did not visit us. We slept

till noon.

With one voice I called him, with one voice

I let him sleep, remembering

summer years ago,

I had come to visit him in the house of last straws

and when he returned

above the garden of pears, he said

our weeping caused the dew. . .

I have borrowed the little boat

and I say to him Come into the little boat,

you were happy there;

the evening reverses itself, we’ll push out

onto the pond,

or onto the reflection of the pond,

whichever one is eternal

HOLY WEEK: THE TRAILER

This Sunday only (!), between the 9 & 11:15 services The Rev. Dr. Ruth Meyers will lead us in a preview of Holy Week. Starting with Palm Sunday, including Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, the Great Vigil of Easter, and finally Easter Sunday, Ruth will give us a glimpse of each service and it’s place in the story with some time to ask questions and engage. Use this as a time to prep for what’s to come. Class will meet in the Parish Hall.

Continuing the Feast

On March 25, Palm Sunday, is a Continuing the Feast potluck brunch. Join us between the 9 & 11:15 services in the Parish Hall and bring some brunch type foods to share!

KEEPING WATCH

We are seeking participants for our Maundy Thursday Vigil. As part of our annual Holy Week practice, All Souls keeps overnight vigil in the chapel with the sacrament reserved from Maundy Thursday. This vigil is meant as a “garden space,” to resonate with the events following the betrayal in the Garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus is taken into custody and interrogated overnight. For our vigil, we are asking parishioners to keep watch through the night, as a community. People often use this time to pray, read scripture or devotional materials, or simply sit in silence. Keeping vigil can be a deeply spiritual experience and a meaningful way to prepare for the mystery of Easter. Please contact Laura Eberly at leberly@gmail.com with your top two time slot preferences between 9:00 pm to 8:00 am to sign up.