FROM THE RECTOR

A Death Chamber, dismantled

Many years ago, when I was an undergrad at Cal and helping out on Sunday nights with a local youth group, we stumbled into an intense conversation about the Cross. And after some time discussing what the Roman Empire used the cross for—deterrence and control through fear—one of the high schoolers asked, “Then why we don’t wear necklaces with electric chairs on them? Wasn’t the cross about a criminal being punished with death?”

I was reminded of that conversation from decades ago as I saw the photos this morning of the death chamber at San Quentin State Prison being dismantled and carted away.

Yesterday Governor Gavin Newsom placed a moratorium on capital punishment in the State of California and a reprieve to the 737 inmates on Death Row at San Quentin. He also directed that the gas chamber and the lethal injection units be closed. His decision has both infuriated and heartened Californians and others across the globe.

I am one of those who had tears in his eyes when viewing the photos and reading Governor Newsom’s words, as well as the words of the families who have experienced devastating loss because of the violent deaths of people they have loved. I believe that ending the practice of state execution is the Sermon on the Mount brought to life.

Financially, practically, and ethically, capital punishment fails to deliver the promises we make with it. It costs significantly more of our tax dollars to keep a person on Death Row with the necessary legal appeals than it does to incarcerate them for the duration of their lives. And there is no evidence that putting a person to death, no matter how vile their actions were, deters other people from committing violence themselves.

But I write this not as an economist or as a sociologist, but as a priest who attempts to live by the study and practice of way of Christ. And I find capital punishment to be fundamentally inconsistent with the life, death and resurrection of Jesus the Christ.

Yes, it is unjustly applied, as a murderer in this state is three to four times as likely to be given a sentence of death if they kill a white person, than if they kill an African-American or Latino person. And yes, we have sentenced innocent people to death, sending them to be killed on our behalf, only to saved by appeal.

And I understand a core frustration that backers of the death penalty have voiced in the last day: that without capital punishment there will be no semblance of justice. What I have come to understand, however, is that killing another human does not bring the closure hoped for, and while it may feed our sense of vengeance for the pain we are suffering, it does not lead to a fundamental change in the world around us.

René Girard, the great 20th century social theorist, experienced this revelation firsthand. Girard grew up in France, a country that has been culturally defined in many ways by Roman Catholicism. But Girard, like many French, had no religious inclinations.

That changed because of his studies in mimetic (or mirrored) violence. Girard saw that throughout human history we predictably returned violence with violence. This stance of retributive violence is famously evidenced in the Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian code of laws from 1800 BCE, as well as in the books of Exodus and Leviticus.

But it was his study of the life of Christ that he understood, for the first time in a way, that this cycle could be broken. To kill another could not break the cycle, but only serve to continue it. Or, in the words of Greg Boyle, the Jesuit who founded Homeboy and Homegirl Industries in Los Angeles, “if you do not transform your pain, you will transmit it.”

This is one of the essential truths of the Cross: that instead of continuing to inflict pain and violence upon others, Jesus, through God, was willing to transform it in and through his own body. Those of us who reverence the Cross must not be willing to inflict our own version of it on others, no matter the transgression they have committed.

I realize that this is a difficult conversation for many, and if the recent ballot measures are any indicator, one that is far from settled for a majority of Californians. I also know that for some, Governor Newsom’s use of his authority was an abrogation of the process of governance.

For this citizen of the State of California, however, knowing that others have been punished with death in my name, Governor Newsom’s decision has offered relief and hope for a more just and righteous common life together.

Peace,

Phil+

REPORT FROM PARADISE

On a recent Friday morning, slightly nervous, I picked up the telephone and called the church office of Saint John the Evangelist Episcopal Church in Chico, California. I have no connection with Saint John’s Chico, and I don’t know anyone who attends church there. I was calling to learn about the recovery work being done in and around Paradise, after last November’s devastating Camp Fire, to ask, “how are you holding up,” and to see what kind of help All Souls Church could provide to help our neighbors. I thought someone at Saint John’s might have some answers. The church website listed office hours of Monday through Thursday, so I planned to leave a message. Instead, Sherry Wallmark, the office administrator extraordinaire, picked up the line. After an exchange of names, I told Sherry why I was calling and asked if she could tell me anything. For the next half hour or more, I learned about how a church and its wider community lift up the fallen, after a devastating fire wipes out an entire town.

On a recent Friday morning, slightly nervous, I picked up the telephone and called the church office of Saint John the Evangelist Episcopal Church in Chico, California. I have no connection with Saint John’s Chico, and I don’t know anyone who attends church there. I was calling to learn about the recovery work being done in and around Paradise, after last November’s devastating Camp Fire, to ask, “how are you holding up,” and to see what kind of help All Souls Church could provide to help our neighbors. I thought someone at Saint John’s might have some answers. The church website listed office hours of Monday through Thursday, so I planned to leave a message. Instead, Sherry Wallmark, the office administrator extraordinaire, picked up the line. After an exchange of names, I told Sherry why I was calling and asked if she could tell me anything. For the next half hour or more, I learned about how a church and its wider community lift up the fallen, after a devastating fire wipes out an entire town.

After the Camp Fire destroyed the town of Paradise, its neighboring city Chico was inundated overnight with 20,000 people in need of food, shelter, clothing, transportation,—everything that makes our material lives operate from day to day. Four months later, thousands of people continue to do the long, hard work of rebuilding their lives. “We’ve been through heroic,” Sherry explained, “when people focused completely on responding to the fire. Now, we’re in the dissolution phase.” We talked about how slowly recovery happens. Even when everyone is pulling together, “this is going to be a marathon,” was how Sherry described the situation.

To respond to the needs of individuals and families, Saint John’s has made gift cards available. People need food, warm winter clothing, propane tanks for heating, and gasoline to drive to work and school. The fund to purchase gift cards has all but run out, and new contributions have dwindled in the four months since November 8, 2018. Replenishing this fund is a way that All Soul’s Church could directly help its sister parish and the victims of the Camp Fire. Sherry estimates that the church has been giving out around $300 to $500 a week in cards. Families typically receive $100 and individuals receive $50. Most recipients only ask for one time assistance. The gift cards help ease the impact of starting over, paying higher rent, making less money in a different job, living further from work and school, and all the added expenses of daily life that result from total, utter, unimaginable loss.

Listening to Sherry was both sobering and inspiring. The stress of long term recovery seems as unbearable as the fire itself. On Sunday March 24, All Souls will take a special collection for Saint John’s Chico. Please donate in whatever way that you can — make checks payable to All Souls with Paradise Fire Relief in the memo line and we will bring them one large check, or bring gift cards they can give out directly. Plans are also underway to deliver our collection in person to the congregation at Saint John’s Chico. Stay tuned for the next Report from Paradise.

— Bonnie Bishop

From the Senior Warden

Whiteness as Heresy

We discovered some surprising things in the Whiteness as Heresy formation class last month.

Most importantly, Margaret Sparks apparently moonlights under the moniker “Director of Good Times.” It is well-earned.

The second realization was something she voiced for many of us in the first moments of the first class; even sitting next to a friend you’ve known for decades, your experience of race can be a new and unexplored conversation topic.

So we explored together. And we’re planning to do more.

And while I shouldn’t be surprised by it anymore, it never ceases to amaze me how ready All Soulsians are to show up to the profound and challenging stuff together.

Over the course of three weeks, we explored how our theology might address questions of race and racial identity, and specifically where our Christian commitment might provide antidotes to a culture of white supremacy. If we viewed whiteness as a cultural, socialized identity rather than an immutable fact of skin tone, might we then hold that cultural identity up against who we believe God calls us to be in Christian community, and decide to do things differently?

Defining culture as roughly “the way we do things around here,” we examined how a culture of white supremacy – a culture that holds the expectations, values, and behaviors of white people as a normative ideal – plays out in our lives.

There was a lot to work with.

From our expectations about punctuality and urgency, to what constitutes “appropriate” dress and self-expression, to rules of “politeness,” standards of perfectionism, and the powerful myths of meritocracy, we found almost every aspect of our lives, including “the ways we do things around here” at All Souls, inflected with the expectations of a white supremacy culture.

And yet, guided by Tema Okun’s work describing the attributes of white supremacy culture, we were intrigued to find that at All Souls people are paying attention to and pushing back against almost every single one. Ministries, their tasks and experiential wisdom, are held collectively. We look for mystery and abundance and multiple ways of being called by God, rather than a single right way to be. We are encouraged to confess, rather than defend.

In short, whether we have named it this way or not, we already have a sense that our faith calls us to reject the defensiveness, either/or thinking, individualism, and sense of scarcity that white supremacy culture engenders and on which it thrives.

Of course, we are not done. Immersed in white supremacy culture as we are, these antidotes can be some of the most challenging aspects of our faith to live into together. So we asked ourselves, what might we do to support and foster that life-giving, counter-cultural resistance to the ways of white supremacy?

We thought it might be apt to do something that is itself life-giving, counter-cultural, even…Lenten. We decided we would not just do something. We would listen.

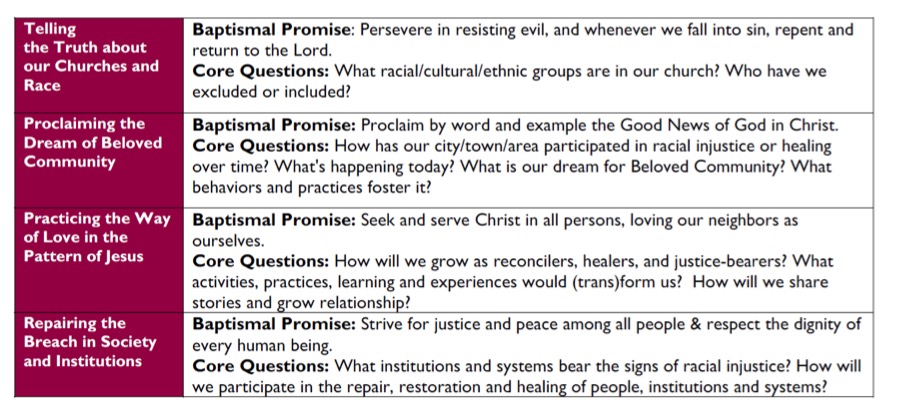

In our final session, we considered the Becoming Beloved Community resources on racial reconciliation.

They are perfect for Lent. Arranged around a labyrinth, each quadrant reflects on a baptismal promise and offers related questions to consider about racial reconciliation. As we prepare to remember and renew our baptismal vows at Easter, as another catechumenate gets underway, we each mediated silently on a question that stood out to us. When we shared which quadrant we “entered” the labyrinth from, the room was organically evenly divided, and we were reminded that it takes all of us to do this kind of work. We each enter in our own way. None of us can do it all, yet it all needs to be done, and together that is possible.

They are perfect for Lent. Arranged around a labyrinth, each quadrant reflects on a baptismal promise and offers related questions to consider about racial reconciliation. As we prepare to remember and renew our baptismal vows at Easter, as another catechumenate gets underway, we each mediated silently on a question that stood out to us. When we shared which quadrant we “entered” the labyrinth from, the room was organically evenly divided, and we were reminded that it takes all of us to do this kind of work. We each enter in our own way. None of us can do it all, yet it all needs to be done, and together that is possible.

So over Lent, we committed to listening to some of these questions at All Souls. We represented many of the All Souls walks of life; parents, choir members, sacristans, vestry, justice and peace ministry members, young adults, elders, youth, white people and people of color, new members and people who have been here for decades. So we are hopeful, if we each listen for a handful of these questions for forty days, and perhaps if a few others join in, that we might collectively hear where the spirit calls us next.

We will come back together in Easter to share what we have heard and wonder together about life-giving ways ahead. I hope you’ll join us.

— Laura Eberly

From the Associate for Music

Firing Devotion

If you worshiped with us at the 11:15 service this past Sunday, you might have noticed that we sang the Gradual psalm in alternation: Cantor’s side, Presider’s side, Cantor’s side, Presider’s side, and so on. In doing this we are participating in a tradition that stretches back over 1,000 years—but not merely for tradition’s sake. In my Ph.D. dissertation I described the history of this practice as well as some of the meanings Christians have attributed to it over the centuries, which can inform our own senses of what it might achieve for us today.

The story begins with one of the core items in our liturgy: the “Sanctus,” or “Holy, holy, holy.” It is a song of praise taken from Isaiah 6:3, where the prophet sees God’s throne attended by beings called seraphim (in the Christian tradition, these are a type of angel): “And one called to another and said: ‘Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory.’” This verse of scripture was important even in the Church’s first few centuries, and orthodox writers like Augustine read it in several ways. Perhaps the most common was to view the threefold “holy” as a symbol of the Trinity. But Augustine also noticed that scripture, in addition to reporting what the seraphim sing, mentioned how they sing it: “one called to another.” He likened this reciprocal exchange to the relationship between the Old and New Testaments, which respectively present and fulfill prophecy.

Fast-forward to seventh-century Spain. One marker of liturgical development in the Christian West around this time is the first unambiguous description of what would remain a daily practice in monasteries and churches throughout the Middle Ages, and is still used in many cathedrals of the Church of England: the singing of psalms alternatim, Latin for “alternately” (one verse is sung by one side of the choir, and the next verse by the other side). The author of this earliest description of choirs singing alternately was Isidor of Seville, who proceeded to channel Augustine in making the further observation that the practice was “like the two seraphim and the two testaments calling to one another.” Isidor thus understood the back-and-forth of mortal choirs as imitating an angelic manner.

Fast-forward another thousand years, to England around the year 1600. The connection between the seraphim and choirs singing alternately was still being invoked. Some defenders of the Church of England, like the theologian Richard Hooker, were even beginning to make broader claims that other kinds of liturgical “answering” (such as “the Lord be with you…and also with you,” which we still say) might also mirror the reciprocations of angels.

I argued in my dissertation that these explanations for singing alternately or responsively drew together several strands of thought. First, one influential theology of liturgy in the Middle Ages held that church music put the faithful in mind of the joys of heaven, and so the notion that any particular musical practice had been derived from angels served as a material manifestation of the basic connections between heaven and earth.

Second, singing in alternation exemplified a larger theory of vocal performance that some medieval and early modern churchmen were developing: the idea was that exchanges of praise, thanksgiving, petition, and comfort between singers, or between the people and their minister, would act as a sort of devotional teamwork, causing a mutual escalation of piety. Hooker wrote that by using “interlocutory forms of speech” in public worship, Christians could “stir up others’ zeal to the glory of that God whose name they magnify.” Other writers explained that the seraphim who called to one another were ideal examples of this. A main reason was that the name “seraph” is derived from the Hebrew verb saraph, meaning “burn,” and was understood to symbolize exceptionally ardent devotion; imitating their mutual cries could thus be conceived as a path toward supremely pious worship.

Drawing on this history, we might use this alternate singing to meditate on the choirs of angels, and to engage in some of our own devotional teamwork. By singing the words of spiritual beings who burn with love for God, and by following their manner, maybe you’ll even experience a bit of heaven on earth.

—Jamie

Accessing the Online Directory

Many of you have had a hard time accessing the Online Directory lately, and for that I am sorry. It is a rich resource in helping us all connect with each other. If you haven’t ever had an account created for you in the church directory, please see me or Mardie Becker and we will add you. Once added, you will be able to follow the links below.

If you’ve already been added to the directory but are having a hard time accessing it, it may be that you need to login once again and create new password. It also could be that you need to erase the app on your phone and re-download it. You will also then need to login once again. Click here to access the directory from you computer. Click here to download the app on your iPhone, and click here to download the app on your android phone.

Still having trouble? Bring your device in to me and we’ll see what we can do.

— Emily Hansen Curran

Continuing in Adult Formation

Join us on Sundays at 10:10 in March for these classes — come for one, come for all!

O, The (Not So?) Wondrous Cross

(Parish Hall)

This course is on a basic symbol of the Christian vocabulary. How can we, as disciples, speak faithfully about the cross? This class will explore the symbol of the cross and its connections to discipleship through the lenses of prayer, social action, and salvation. The class will be taught by our own Dr. Stephan Quarles, who has just completed a PhD in theology at the Graduate Theological Union.

Eros and Eucharist for Easter: Setting the Table with Transformative Love

(Common Room)

If “God is love” is God also “Eros”? Can erotic desire deepen Christian meanings of love? Do contemporary notions of eroticism make any difference in how we read biblical texts and Christian traditions? What is love? What is the erotic? How might these questions frame the Eucharistic table on our Lenten journey toward Easter? This Lenten series will explore the role of erotic desire in patterns of spiritual formation, especially in our shared calling to the work of social change and transformation.

The class will be taught by the Rev. Dr. Jay Emerson Johnson, who is an Episcopal priest and Assistant Professor of Theology and Culture at the Pacific School of Religion and a core faculty member of the Graduate Theological Union.

Parent Feedback Sessions

March 17th at 10:15am and March 24 at 12:45pm

We want to know from your unique perspective as parents how you feel children’s formation is working at All Souls now! Whitney Wilson has been working with us for several months to take a close look at how we do Children’s Ministry here, and she is excited to do a deeper dive with you all, to gather your wisdom and perspectives as parents for our youngest members. Whether you have been attending All Souls for ten years or two months, your opinion is valued as a member of the All Souls community. Parents are invited to come to one of two sessions: Sunday, March 17th at 10:15am (for about 45 minutes) and then again on Sunday March 24 at 12:45pm. (for about 45 minutes). Please join us!

CAMP ALL SOULS – REGISTER NOW!

This summer we are bringing back Camp All Souls, a week-long day camp for kids to adventure, connect, explore, learn, play, create, question and more, all right here at All Souls. This year the camp will be August 12 – 16. It runs from 9:00 am to 3:00 pm and is for kids ages 5 to 11, who have completed kindergarten through fifth grade. Cost is $150, and scholarships are available. Once again, we will be welcoming middle and high school students to help lead the week, as well as adults who want to pitch in – it is a whole community affair! You can learn more and register online here or pick up a paper registration form in the narthex.